WHY I WRITE – by Linda Nemec Foster

Linda Nemec Foster’s essay is featured on the website, Write Across Chicago, which is sponsored by the Illinois Writing Project based at Northeastern Illinois University. A member of the Society of Midland Authors, Linda is the only non-Illinois resident featured on the website.

To read the full article, please click here!

WHY I WRITE – by Linda Nemec Foster

ON WRITING

By Linda Nemec Foster

I write because I want to connect with others. I’m primarily a poet and I love poetry for the powerful way it uses language and the blankness around line breaks and stanzas to reflect metaphor, imagery, tone, rhythm, and pacing. Poetry is the only kind of writing where what you don’t say (think of all that white space on the page that surrounds a poem) is as important as what you do say (the language that encompasses each line). And when a poem is read out loud–connecting it to that ancient oral tradition that was the precursor to all written literature–the process is complete.

I also write flash fiction and prose poems that balance the tone between narrative and lyric voices. I like to work with this dichotomy: it’s an ambitious exercise but when the piece can achieve that balance between a narrative arc and strong lyricism, it’s nothing short of magic.

When I’m starting a new poem, I’ll write the first drafts in longhand on a yellow legal pad or a standard notebook. On average, this process of early drafting can result in five to ten rough drafts; that is, every poem I create begins in drafts of at least five to ten versions. After I determine that the piece has achieved a decent structure of form and content, I take the most recent draft and type it on the computer. The revision process continues as I see how the structure evolves as a typed piece. This is particularly essential for poetry as line breaks, stanzas, and section breaks are readily formatted on the computer screen. Currently, a lot of poets and writers prefer to compose directly on the computer but I’m “old school.” I love to feel the paper, to hold the pen, to cross out words and add lines. It’s a tactile and visceral experience for me and I wouldn’t have it any other way. I know the computer is essential for final revisions but that initial creative spark–the first drafts–are always handwritten.

My work of being a poet, a writer, and now (after eleven published poetry collections) an author has enriched my life in ways that are inestimable. True, there is no money in poetry. But the intangible rewards are gratifying and humbling. The most amazing situation I experienced as a writer was when I received an email from a person I never met. This woman had purchased one of my poetry books–a collection of haiku and visual art–that was a quiet meditation on nature and our place in the natural world. Every day she would read excerpts from the book to her friend who was in the advanced stages of terminal cancer. The poetry gave both of them a sense of peace and serenity as one life ended and one life carried on. No award or recognition could match the significance of those words from that stranger.

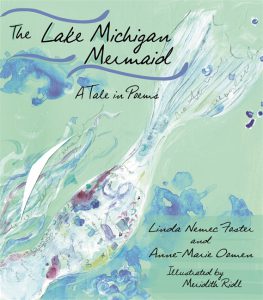

Linda Nemec Foster is a poet, writer, literary presenter, and founder of the Contemporary Writers Series at Aquinas College. She is the author of eleven collections of poetry including The Lake Michigan Mermaid (with Anne-Marie Oomen), Talking Diamonds, Amber Necklace from Gdańsk, Listen to the Landscape, and Living in the Fire Nest.