Reviewed by: Diane Sahms-Guarnieri

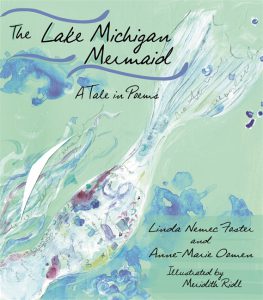

Linda Nemec Foster reiterates this real and imagined theme of yearning and self-discovery throughout the four sections of Amber Necklace from Gdańsk.

.

In poem after poem of sculptured landscapes of Old World and New, of Poland (before WW I) to USA of today, Linda Nemec Foster yearns for wholeness, yet knows that this severance of self the “she” (“the other self”) from the Old World will be never be found “in the New,” as in the appropriately titled poem, “Doppelgänger” she writes:

…A mere roll of the dice that I’m here

and she somewhere else

.

…because a simple act of birth that place me

in suburbs south of Cleveland and

not in a town across the river from Oświęcim

.

The last line of the poem puts the reader at a screeching, yet realistic halt:

…may we never recognize each other on street.

.

Is this an acceptance of harsh reality, of being born in Cleveland, Ohio “on the opposite side of the world” to first generation parents (whose grandparents left Poland) and the realism that she will never be able to experience or have lived the life of “the other self.” I believe the last line of the poem is realistic; however, within every artist/poet there is imagination; there is the “what if” question; there is the wishful desire to have that which you know you can never really have. As if, perchance, there could have been a meeting of the “other self,” that is if Fate could have allowed her to live a different life (she never knew), a life she could never truly know. Yet, the fact is she was destined to live here in Ohio, in the New. It is this longing that exists – to have known a different life, to have been given an opportunity to be a different self “other self” in this opening poem that stays with the reader especially because of the powerfully ironic last line

…may we never recognize each other on street.

.

Can one re-unite the two? No, never, and if we could then would we be better off not knowing what life would have been like anyway. A bit paradoxical? Absolutely! The “longing” to be someone we could never be, yet at the same time thinking we should have at least had a “chance” at it. A choice, perhaps This is the unknown, the not knowing (that can never truly be satisfied); and that which a second generation girl/woman ponders, especially when one is blessed/cursed with a creativity poetic mind. A mind that questions.

.

This is a book of interconnected narrative poems with an undertow of longing for a life we can never have. Therefore, the second poem, “Doppelgänger,” has set the stage for the remainder of the poems in this collection. The fact is she was born here, but her love is reflected in poems about a family she knew and a family she will never really know.

.

The poems roll into and out of each other with a constant pulling undertow of longing, which is never understated in her poems about people and places. Each poem beautifully written, beautifully sad, hurts the reader deeply, because there’s a void which cannot be filled. Especially evident in the poem,

“The Immigrant’s Dream” where each of the three stanzas begin with “a recurrent dream” and ends with a woman’s voice whispering two very strong final words: “You’re home.”

.

This wise archetypal dream woman trying to offer closure tells the immigrant “you’re home” to give the disconnected speaker peace, resolution. Yet, there really is no peace, no closure for three generations of women, who must live without a sense of true peace; and it’s not just the woman speaker, who is displayed but it is her grandparents, parents, and her own son that carries the burden of loss.

.

This sense of loss, in more detail, is also relevant in the poem, “Young Boy in a Tenement House, Holding the Moon.”

He is anonymous as a fairy tale.

His bare feet could be my father’s

or perhaps my son’s…

.

the speaker’s father and / or son’s feet, and as the poem continues it includes the boy’s mother –

his mother five flights up

keeping six kids at bay, waiting

for that basin of water…

.

So it is at this turning point of generational weariness that a child sent for water for an awaiting mother and a large family of siblings that the poet allows the boy to express his inner feelings. The boy in this poem uses his imagination to cope with the un-copeable and this is where Nemic Foster has the young boy’s basin become the moon. The reader knows a round basin resembles a full moon, but what is so poetically crafted here is that the boy

.

…smiles/ not for the camera, but to himself, as if he’s holding a captured moon

.

Here the “moon,” may appear subtle, but to Nemec Foster it not subtle at all, rather the skilled use and choice of the word “captured.” It is not used as a verb here, rather an adjective, and not a “capturing” moon,” but a “captured moon,” as if the child and his entire family residing in a tenement were in a “captured” state of existence, as new comers to a foreign land (America in lieu of Poland). The moon is metaphorically alone in the darkness and “captured” (involuntarily) in a gravitational orbit. Poland is now dead to him as the moon, as the “captured moon.” Captured defined is “to take into one’s possession or control by force.” Now, pushing the envelope further, the boy whispers to the moon,

and whispering to it, his breath

lost in its silver and dust:

księżyc, księżyc, latać, latać, daleko.

.

And before the translation, the poem is interrupted by an foreign language (Polish), not English, because the boy and his siblings, mother, and possibly his extended family (grandparents, great-grandparents) are all displaced in America, not only by their residence in a tenement house, but by language itself. Now, the last two translated lines in English, as the last to lines of this poem:

Moon, moon, fly away, fly away,

and please, take me with you.

.

Here, the child’s plea, “please take me with you” to my real home, because the moon can see all, Poland and America, and the child is homesick for something he cannot have.

.

The aforementioned poems are in the very beginning of Section I – Conjuring Up the Landscape and in continuing in that section Nemec Foster writes poems about her father learning to count in English; immigrant child at school; “The Old Neighborhood”; her mother, “The Silent One,” etc. and ends the section with the poem, “Sitting in America at the End of the Century” with these last very painful lines (both in Polish and English) addressing her grandparents (Maria and Tomasz, Zofia and Franciszek)in the poem’s last stanza:

… A distant granddaughter surrounded by cars,

longing for a language that’s more akin to damp

earth than linguistics, stuttering in a tongue

so natural to them they know what she’s trying

to say, even before the halting words

leave her lips. Bardzo mi przykro,

nie wiem. I am sorry, I know nothing.

.

A real page turner, so captivating that you, the reader, become engrossed with each poem, as I have; but you must continue onward with a reverent, dirge-like pace through the remaining three sections, as they will hypnotize you as well. She is allowing their voices and her voice to be heard, so you can learn of the honesty, integrity, and beauty of each lived life. These narrative-memoir poems tell the familial immigrant stories of her grandparents and parents and also Nemec Foster’s very own second-generation story of, mentally and physically, crossing the Atlantic from America to Poland and then back to America again.

.

Since I have elaborated in Section I, I will try to consolidate the remaining three sections, and this is not to diminish those sections, no, not at all, but in order not to make this – a too long review.

Section II – The Rivers of Past and Present; Section III- Dark Amber of Regret; & Section IV – To Smile at the Closed Mouth of Loss will keep the reader totally engaged. I will pick one poem from each section to focus upon, as briefly as I can, in order to do justice to both poet and poem.

.

Section II– The Rivers of Past and Present has four prose poems, with the exception of the poem, “The Two Rivers in My Story.” Once again these poems do not spare the reader their emotional empowerment, with an intense flow of prosaic images, narratives, and truths felt by a transplanted poet. America’s Cuyahoga River aligns, yet conversely misaligns with Poland’s Vistula River – just as the past aligns, yet conversely misaligns to the present, at least in Nemec Foster’s telling of rivers and time in her prosaic poem, “The Women with the Two Rivers Growing from Her Hair” (wonderful title). Here, Nemec Foster recounts a “true” story told to her by her mother about her grandmother, Maria.

.

…I know it’s true because my mother told me that her mother saw it with her own two eyes.

.

Interestingly enough, oral history imagined or true is prevalent among immigrant families and serves as a connective thread often linking one generation to the next, especially in this story of women.

.

Maria, my mother’s mother with green eyes who died long ago, whom I never knew, but could only imagine.

.

Without giving the total story away here are some lines of her grandmother’s story told by Nemec Foster’s mother to her, whereby the flow of the women of her family and the flow of rivers align and misalign with each other.

.

One day she decided to leave her mother, her father, all her sisters and brothers, aunts, uncles, cousins, and friends and come to the New World and live in America.

.

Her grandmother settled in Ohio in a boarding house near the Cuyahoga River and it took her weeks to pronounce the river’s name.

.

She especially loved the sound of the city’s river, Cuyahoga, even though it took her many weeks before she could even begin to pronounce it. …As if trying to will the river into her tiny bedroom on the third floor of Mrs. Okasinski’s boarding house.

.

The grandmother’s dream of the Vistula River in Poland, where she turns into a mermaid. A straight up metaphor, why, because oral tradition and the imagination usually go hand-in-hand.

.

She was a mermaid swimming in the deep, clear waters of her homeland, the Vistula River. Her legs had turned into one huge fin, her beautiful hair had become filmy seaweed. Even her green eyes had turned into the blue-white of mother-of-pearl.

.

Nemec Foster hits the comparisons hard: Old World – Poland vs. New World – America; Vistula River vs. Cuyahoga River; the Past vs. the Present; and then with her brilliant choice of poetic language, the Simile

– “like” for comparative purposes.

.

The Vistula flowed around her like scattered diamonds. For the first time since leaving Poland, she felt homesick. In the morning when she awoke, the rain was still falling, like drops of a river from the sky.

.

In finishing this comparative poem, there’s unification and /or a blending of the two separate entities into the one identity, separate but united in the poem’s summation:

.

Her long, golden hair had explicably transformed into the two rivers she loved so much: blue Vistula of the fish-maid; green Cuyahoga of the exotic song. They flowed from her head like twin cascades of the past and present, the old and the new.

.

And finally Nemec Foster’s heart wrenching metaphors provide hidden similarities between her grandmother and / or immigrant women and their descendants, directly and poetically equating them to river/water images:

.

Some say the woman disappeared into the rivers that claimed her. Some say she walked into the rain and became the rain. And some refuse to believe that a woman’s hair can change into the waters of two rivers by mere act of a strange dream. But then, they don’t know the woman.

.

Section III- Dark Amber of Regret succeeds II, but not with prosaic poems, rather 13 shorter poems. These poems – move the reader along the high wire of regret and longing, looking at each side Old – New, Poland – America, as if the speaker, a high wire walker were treading very carefully in a world where a fine wire-thin-line exists; and they must forever walk the path of an “examined” life with no real resolution, one always existing alongside the other. This disconnection between two world’s trying to connect is stated in the first lines of the poem “Moje Rozwiane Włosy” where the East is separated from the West:

.

Beyond any control of the East /West border,

Oder/Neisse line, the arbitrary demarcations

of free market and fixed economy, my hair

.

Here the speaker, I, uses the image of her “hair” to connect her.

At the beginning of the poem:

.

…my hair

my hair has become wild, electric halo that refuses…

and at the end of this poem:

…My hair, my wild hair,

wanting to be a braided rope that connects the two.

.

The hair image of the “I” speaker resonates back to the grandmother, Maria, and her “long, golden” braided hair (Section II, above). The speaker (probably Nemec Foster, herself) using a very womanly image of her hair is trying to connect the disconnect. Actually the braiding of three long individual strands (daughter, mother, grandmother) into one braid connects the three women together in their two distinct worlds.

.

I would be remiss not to state that Section III’s poems are extremely musical as a whole. Many stanzas like verses of songs binding many voices together, as if each poem the voice of an instrument, a symphony playing melodiously together. Lovely musical titles too, and poems enriched with naturalistic settings containing names and colors of flowers and trees, such as “Mazovian Willows – Chopin’s Nocturne, Opus 9” (Chopin exiled from Poland); “Song of Sorrow – On Listening to Gorecki’s Third Symphony “ (written as a rhythmic Villanelle); “After the War: Purple Flowers Spilling from the Window;” etcetera. There is one very daunting poem, “Chapel of Skulls – Czermna, Poland” that does not fit the uplifting musical category of many of the others in this section. It is realistically and humanistically devastating, more funereal. I believe this poem a silent reminder to Nemec Foster that despite her families disconnect from Poland, there would be nothing more terrible then for her family to have been in Poland during WW I and WW II. Not just our own deaths, as the poem reminds us in America and Europe, but the reminder of the

…mass graves at Katyn

or the empty crematorium at Auschwitz

can prepare you for this.

.

Nothing can ever really prepare you for “this” meaning death.

.

Further, the last poem of Section III is the book’s title – “Amber Necklace from Gdańsk” and this poem echoes back to the braided hair, but this time three

.

strands of the past braided around my neck.

White amber of memory, gold amber of song, dark amber of regret.

.

So, three colors of amber as memory, song, and regret are braided appropriately, as title of this book of poems.

.

Section IV – This last section moves through character and place poems, but the reader is struck by the last three lines of the last poem, “Dancing with my sister.” Here the poet not only echoes back to this Section’s title – To Smile at the Closed Mouth of Loss –but concludes the book appropriately as follows:

We glow because we came from the same burnt-out dream

of second-generation immigrants and learned to smile

at the closed mouth of loss and dance, dance, dance.

.

Linda Nemec Foster and her sister have truly learned to smile despite loss and the reader gallops along with Linda and her sister “to the Beer Barrel Polka” with “RESPECT” for the glowing women they have become in America. In the second-generation immigrants’ fight for recognition, Linda Nemec Foster has won the braided Amber Necklace from Gdańsk glowing with three “tears (tiers) of the sun” around her neck.

Originally published by North Of Oxford